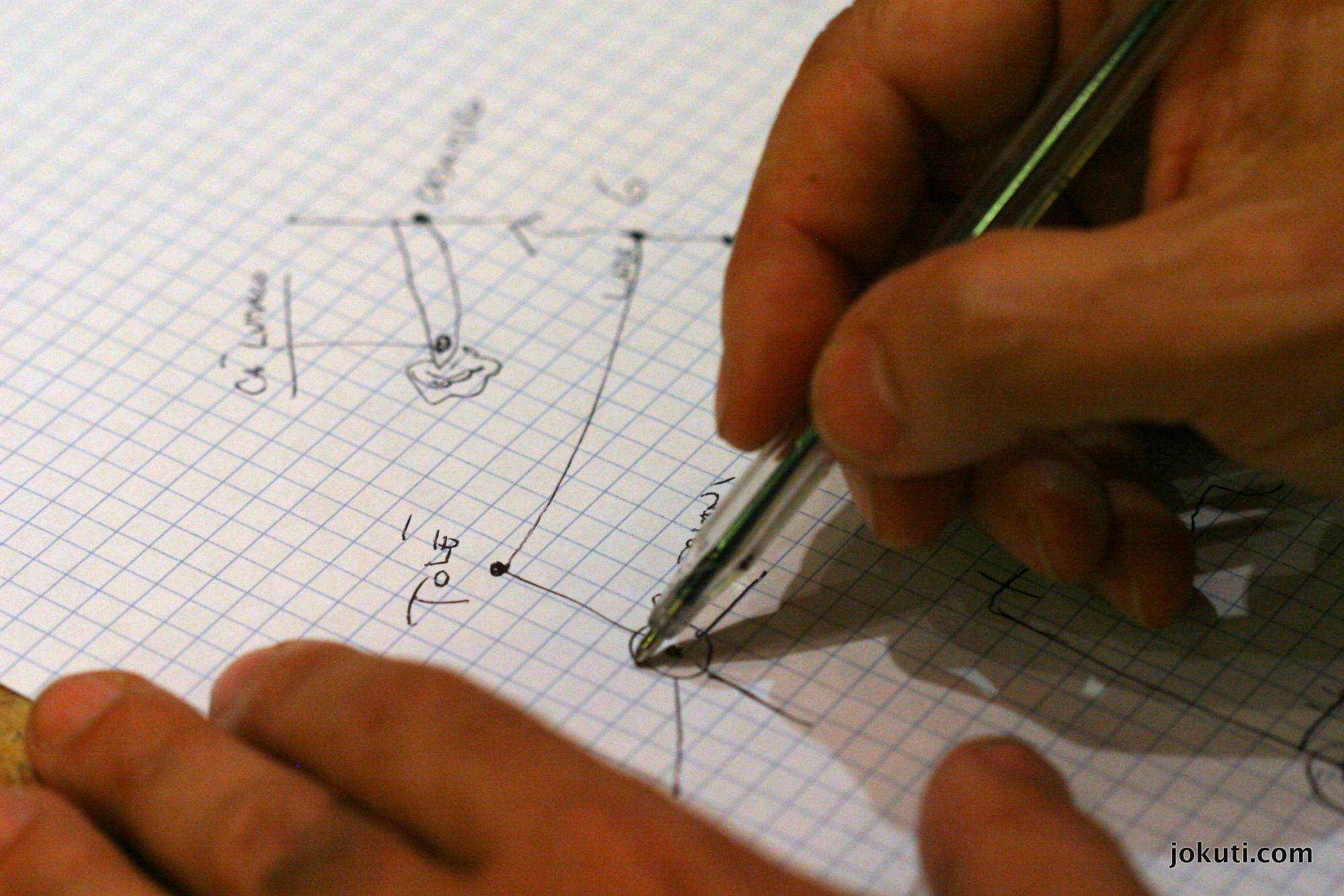

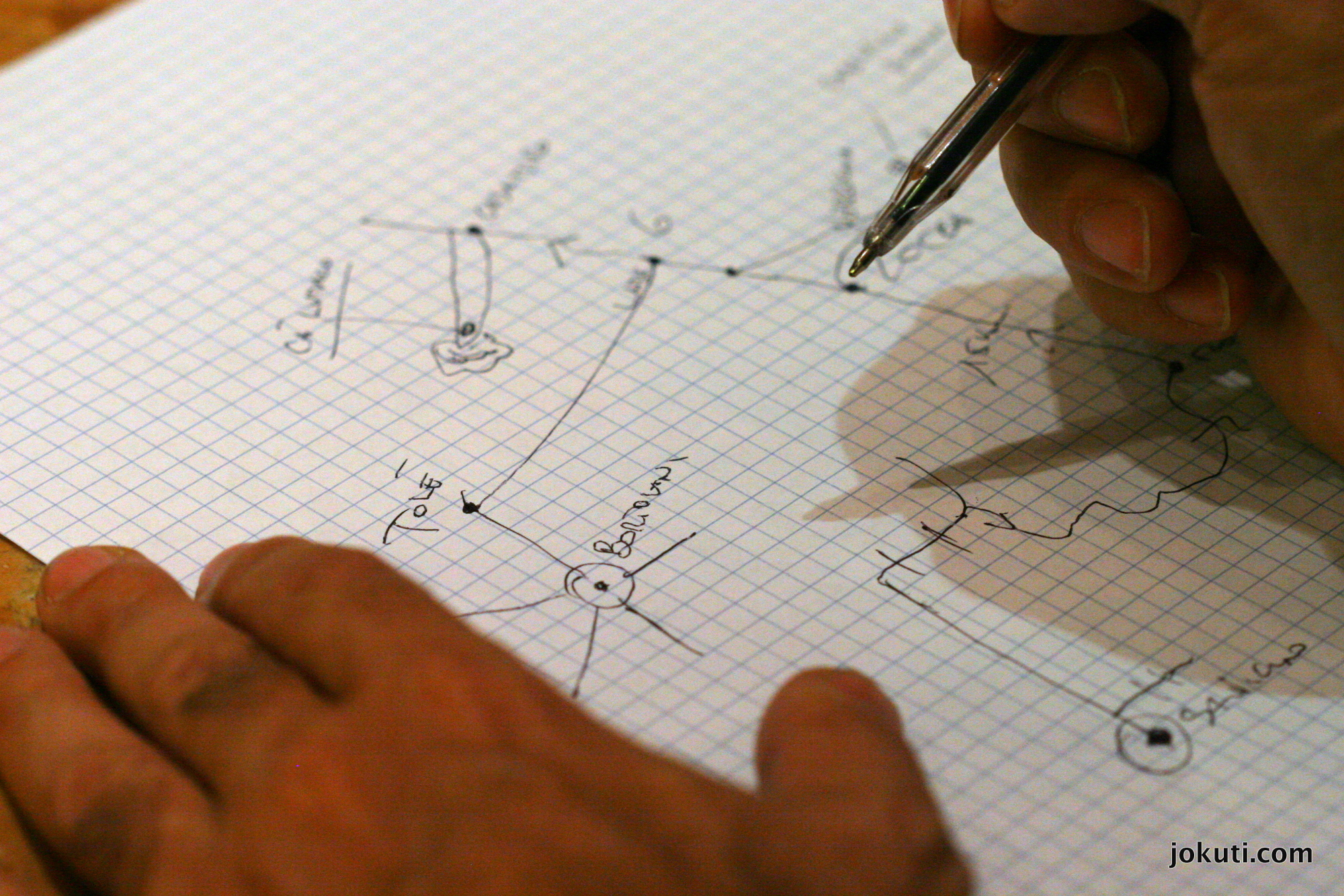

You eagerly pay attention when a chef of a Michelin starred restaurant draws you the way to find the best cheese makers of the area. Especially if you already tried to see them once, years ago, but a sudden snowstorm in March ruined your foodie adventure.

The Amerigo 1934 near Bologna is remarkable because it managed to realise what most of the restaurants are only dreaming of: it sources all its ingredients within a 30 km radius. Even the parmesan. It is a growing trend in many parts of the world to use local ingredients. Not so long ago, it was still trendy to source exotic fruits, fish or even meat from the other half of the world. But today, it is noteworthy if a restaurant is only based on local sources, producers. The logical consequence is that the offers follow the season, the guests and the chefs choose from what is freshly available on the market. This is a good challenge, but it is also beneficial from an environmental and sustainability point of view. Unfortunately, this is not as easy in Budapest. Even if there were producers in the surroundings, the quality matters, too. But the situation is not better in other towns of Hungary either. Let’s hope this will change for the better soon. For the moment, Ikon in Debrecen offers a “30 km menu” as an interesting experiment. The above-mentioned restaurant in Savigno is in a special position because the region of Emilia-Romagna in Italy is home to many world famous products, and most of them are even protected. One of them is the most amazing cheese of the world, the parmesan or Parmigiano Reggiano in Italian.

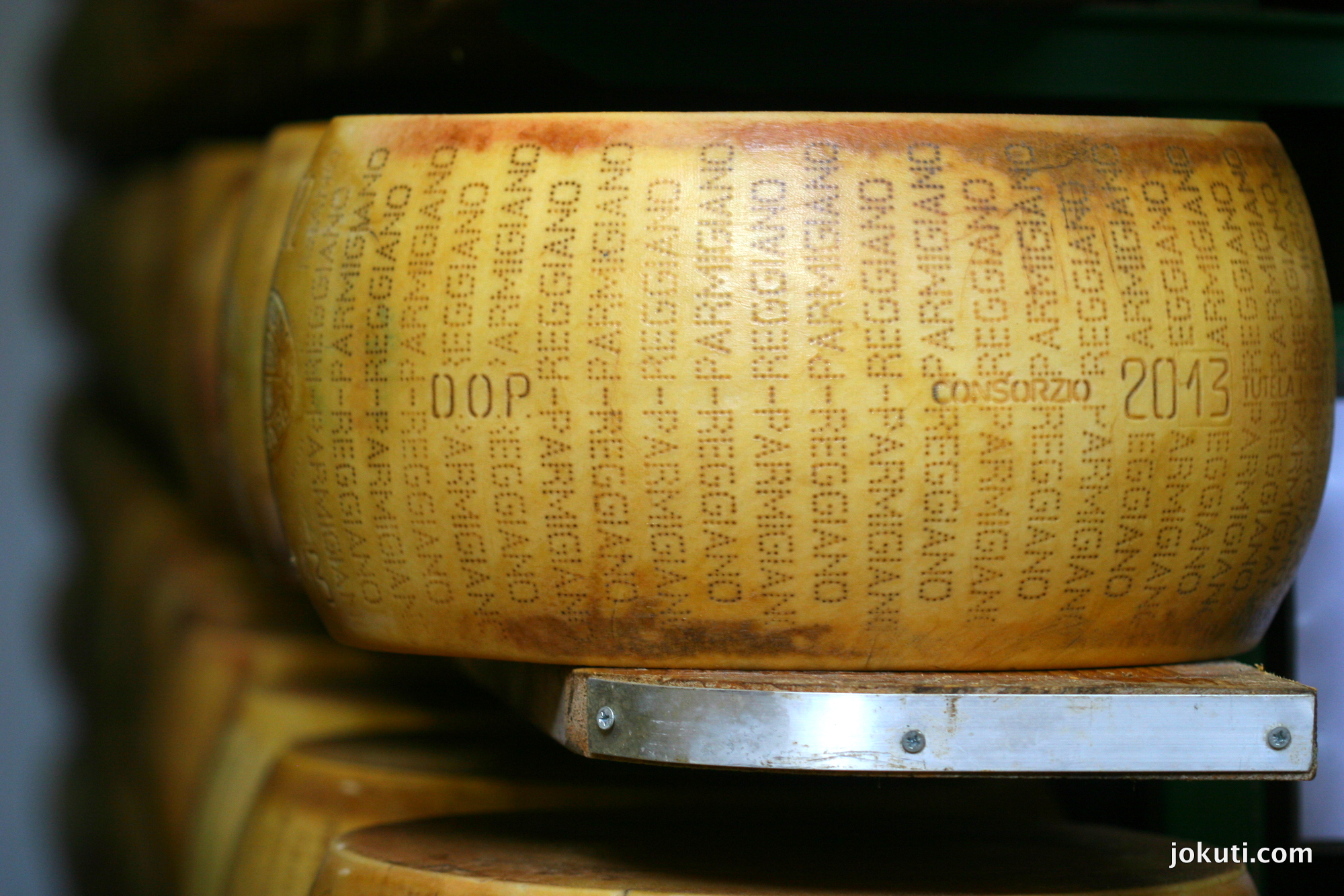

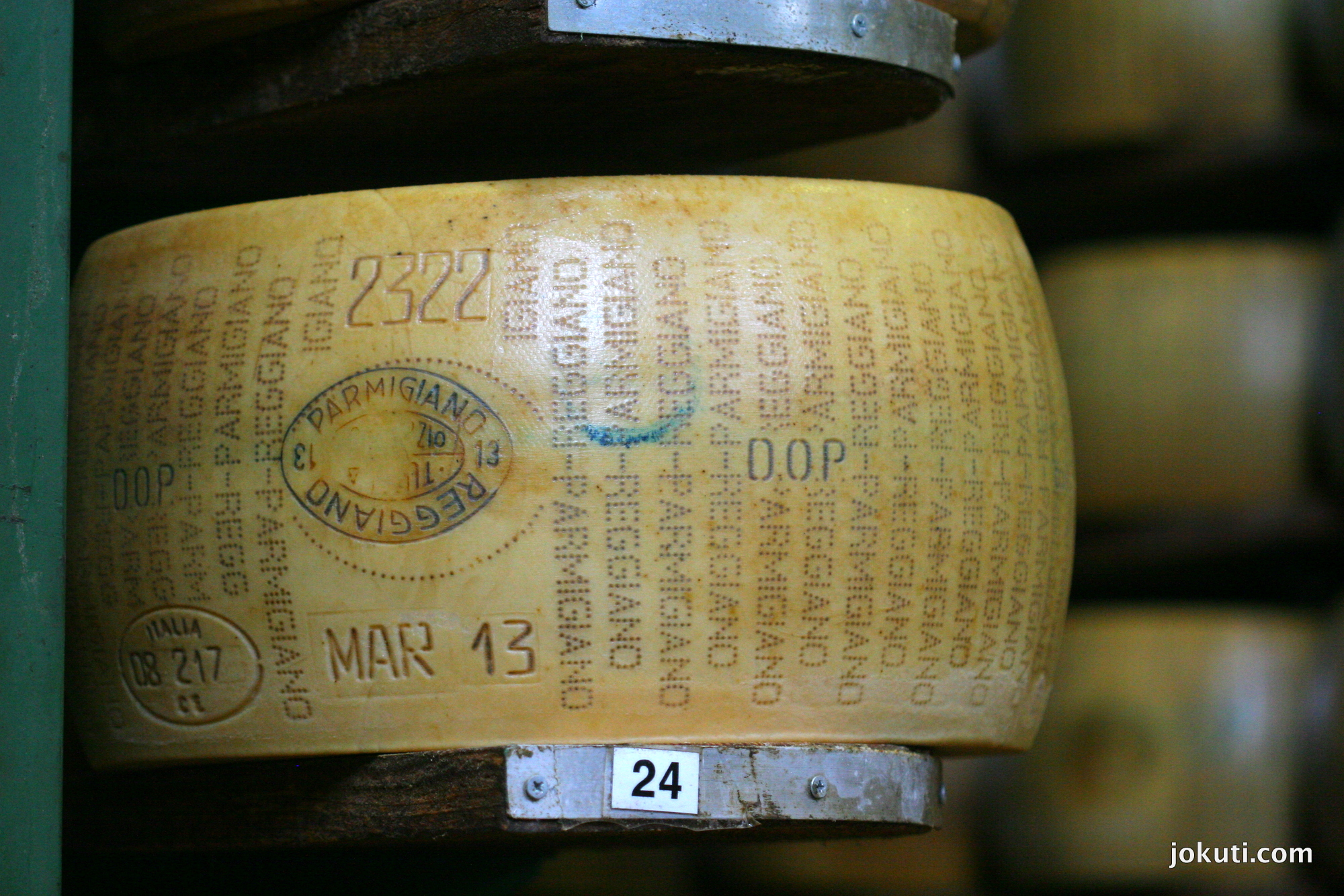

If you think the grated parmesan available in supermarkets, the Grana Padano, or other parmesan-like hard cheeses are the same as parmesan, I advise you to visit immediately a good gourmet shop and try a real, at least 2 or 3 years old parmesan. Preferably one labelled with the stamp of one of the parmesan consortiums on the side, and yes, it has to have a side as well. And don’t get scared if you find small, white, crunchy little pieces, called crystals, inside the cheese. That’s normal, they evolve during maturation (because of an amino acid), it is not a quality problem, and on the contrary, it indicates high quality.

The region of Emilia-Romagna is magical, especially if you keep away from the highways and instead choose the smaller serpentines taking you through the mountains. There were no numbered roads on the little handwritten map but Alberto drew skilfully the supply route that his uncle ('il mio zio') regularly follows. A few years ago, we almost managed to join him for his trip. He only speaks Italian but he does so with so much enthusiasm that I was sure that he could have clearly explained even the tiniest little details of parmesan making. But then, Savigno, also known as the capital of truffles, and its surroundings were covered in snow within one night. Thus, instead of the steep mountain roads, we only got to see the uncle shaking his head... This time there were no obstacles, and in the possession of the perfect map we started our treasure hunt.

Blessed are the cheese makers

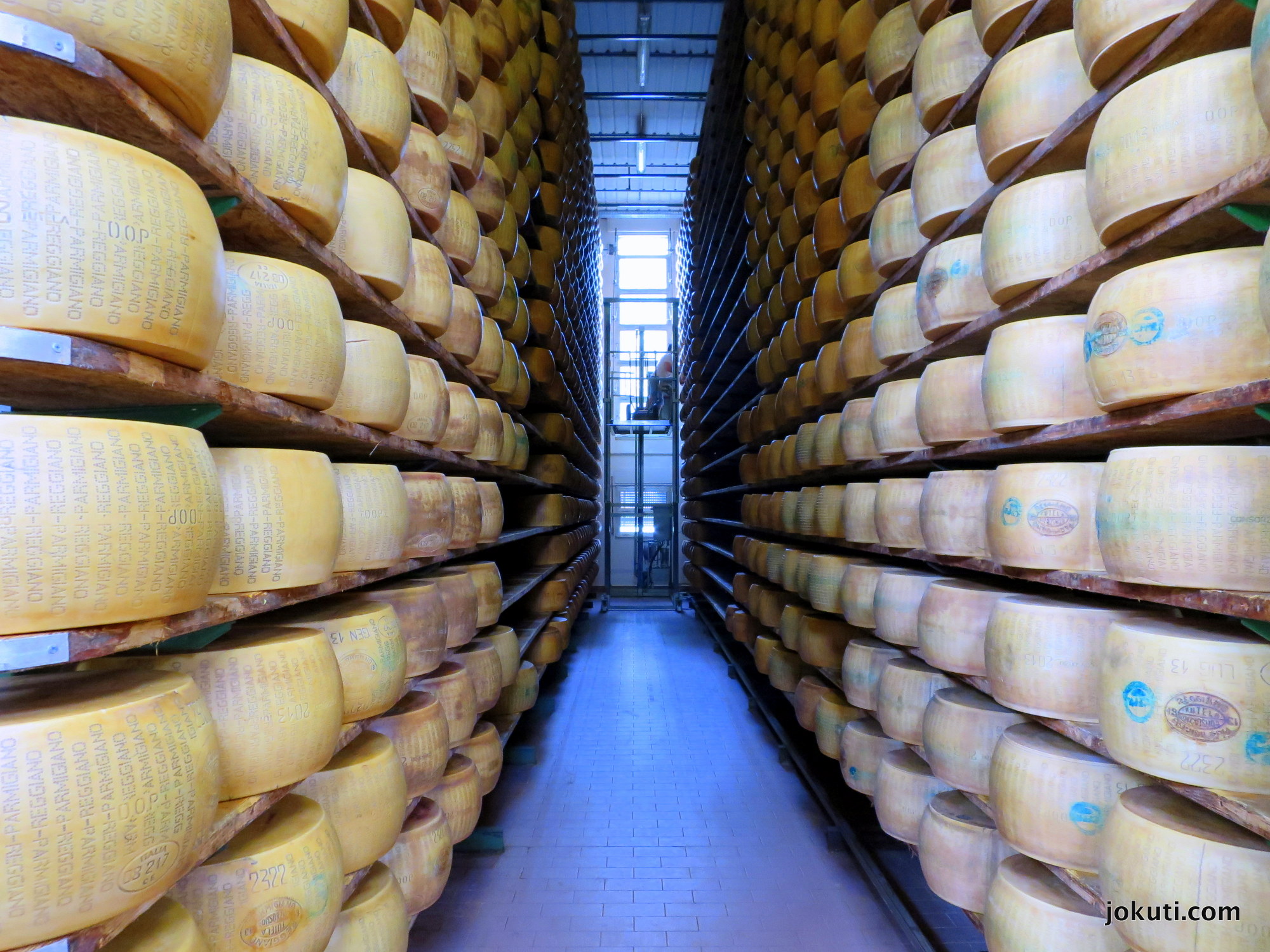

Making parmesan is not a quick way to wealth. Surprisingly, the most important requirement is a huge, well-aired storage room with good amenities and lots of patience. Because even if the milk is excellent, the facilities are professional, the knowledge and the century-old traditions are there, the cheeses still need a lot of time and space. Firstly, for the immersion in a water and salt-saturated solution, which the cheeses swim in for weeks. The cheese maker is a pool supervisor as well: he makes sure that the salty solution is covering each cheese and rotates them accordingly. The experience of long years and a special marking system help him. After the thorough bath, the cheeses are transferred to the shelves of the maturation rooms where they are kept for a year at least. Meanwhile, they go through regular quality controls (knocking on the cheese and taking samples are the two methods); those which don’t meet the standards will get a mark on the crust: failed, cannot be sold as Parmigiano Reggiano. Luckily, this happens very rarely because one single cheese wheel needs an unbelievable amount of milk: 550 litres of milk is used to make a 39 kg wheel, which means 15 l/kg.

But let’s go back to the roots! The milk arrives in the factory and the work starts immediately. You have to know that strict rules apply for the milk and for the cows as well! The cheese can be made only of the milk from cows held in the specified regions and fed with hay only. The breed of the cows is not regulated. At the Caseificio Rosola, where I was directed to, they use the very rare Bianca Modenese breed to produce the special mountain parmesan.

Here comes the bad news for the hard-core vegetarians: to start the cheese making process, they use an enzyme and according to traditional methods, this enzyme is from the stomach of newly-born animals, in the case of parmesan, from veal rennet. This starts the milk to separate into curds and whey. This latter is not wasted either, it’s used to feed local pigs and also humans in the form of ricotta, which is a very important side product of the parmesan making and is in fact not a cheese.

Maybe we can skip the details of the cheese making, the temperatures. The most important is that it is cooked, let to settle and stirred in huge cauldrons during 1-2 days. The cheese mass is removed and wrapped in a traditional cloth. After having strained it, the cheese will then be placed in a mould, which will give it its final shape. It rests there for a few days while a natural crust forms (that is parmesan as well; don’t waste it by throwing it away. The Italians are using it in soups or in grated parmesans!).

This is the moment when the individual cheeses get “labelled”, which displays all the information required but most importantly that it is a real Parmigiano Reggiano. Nevertheless, it can lose this title later if it fails at the quality control. During the whole process, an expert cheese maker, a Casaro in Italian, is needed. He is responsible for the fine tunings because for example the acidity of the different types of milk can vary. Just one hour after the cheeses have been unmoulded, around noon, the whole factory is shining again after the two tireless employees cleaned everything swiftly.

Right after comes the already mentioned 34 week long salty bath. From that point the cheese needs less care because the long maturation process starts. In the huge maturation rooms, an unbelievable amount of cheese is maturing. Just like during the bath, they still need to be turned but only seldom. It’s very rare that a cheese is matured for more than 3 years but here they have a real curiosity: they sell a 120-month-old, i.e. a 10-year-old cheese. However, it is a bit pricy (50 €/kg), so they sell it in pieces only and not the whole wheel. Even among Italians it’s a big feast to eat a 3 year old parmesan but I tested a local dog: he didn’t think twice and ate the piece of the 3 year old parmesan I threw him.

In case we don’t give it to a dog, I’d recommend to maximise the joy and feast on the best quality as it is, on its own. It is especially true for the 36-month-old cheese; eat it cut in bigger chunks with a bit of balsamic vinegar of Modena. But the topic of balsamic vinegar is at least as complex as the one of the parmesan. Most important is to check the labels. It is not enough to look like a balsamic vinegar; it has to be one. Unless you are happy with a vinegar boosted with additives, colours and sugars. The mark to look for is Aceto Balsamico Tradizionale di Modena D.O.C. and the shape of the bottle helps, too: it exists only in one shape. And also the price will help to recognise the original one. Quality has its price, just like in case of the parmesan. After our trip, we still returned to Savigno to say thank you for the great tips (the flours from the doctor’s hand operated mill would require a separate post) and of course, I couldn’t miss one of the big favourites, the “spaghetti bolognese”, i.e. the dish the locals eat: the tagliatelle al ragú. Which they never eat with parmesan, but maybe with a bit of raw purple onion.

Places mentioned: a smaller dairy factory near Bologna, the Michelin starred restaurant in Savigno, the special artisan mill: Il Mulino del Dottore, the balsamic vinegar: Antica Acetaia Villa Bianca.

Your comments are welcome!

Follow/contact me on Instagram and Twitter!